Two reminders:

- Want to improve your Python, Git, and Pandas skills in a small group that I personally mentor — with a clear syllabus and tons of practice? Cohort 8 of my Python Data Analysis Bootcamp (PythonDAB) will start on December 4th. Watch the recorded info session at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pTDP9rSv75Y, or sign up for an interview about the bootcamp at https://savvycal.com/reuven/pythondab . Full info is at https://PythonDAB.com .

- I'm holding a Black Friday sale for new subscribers to my LernerPython+data membership program who get an annual membership. Use the BF2025 coupon code at https://LernerPython.com . This sale only lasts through Monday, December 1st, so don't wait!

This week, we looked at data from the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), to determine when Americans travel the most. Obviously, TSA information doesn't cover car, train, or bus trips. But if we use it as a proxy for general travel, then we can better understand how many people travel around Thanksgiving, and determine (with data!) whether Thanksgiving is really the busiest travel time of the year.

Data and five questions

This week's data comes from the TSA's "travel checkpoint numbers" pages, based at https://www.tsa.gov/travel/passenger-volumes . That page shows, in an HTML table, the number of passengers screened by TSA for each day of this year. Other pages, to which there are links from that main page, have similar data for each previous year, starting with 2019.

Learning goals for this week include: Scraping data, combining multiple files, working with dates and times, grouping, and plotting.

Paid subscribers, including members of my LernerPython.com membership program, get the data files provided to them (except for this week, since retrieving them is part of the task), as well as all of the questions and answers each week, downloadable notebooks, and participation in monthly office hours.

Here are my five questions for this week. My Marimo notebook and a link to view it in Molab are both at the bottom of this issue.

Retrieve data for all available years from 2019 through the present from the TSA's site. Combine that data into a single, one-column data frame in which the date is the index and the number of passengers is in the Numbers column. Create a line plot showing the number of passengers who passed through.

I started by loading a number of modules that I would use:

import marimo as mo

import pandas as pd

import requests

from io import StringIO

from plotly import express as pxWhy so many packages:

- I imported

marimo, since it is basically mandatory inside of Marimo notebooks - I imported

pandasto actually analyze the data - I imported

requestsandStringIO, because – as we'll see – they are needed to retrieve the data from the TSA's site - I imported

plotlyfor the plotting tasks.

My original plan was to use the Pandas method read_html to retrieve each of the HTML tables on a Web page. Using read_html on the current page, as well as pages for previous years, would give me the information in a data frame without having to work too hard.

I would need to retrieve from a number of pages. I thus created a Python list with all of the URLs from which I would want to download data. I started with the current data, which lacks a year, and then used a for loop along with range to get additional years' pages:

urls = ['https://www.tsa.gov/travel/passenger-volumes']

for year in range(2024, 2018, -1):

urls.append(f'https://www.tsa.gov/travel/passenger-volumes/{year}')However, when I tried to run read_html against the TSA's main (current) page, I got an error message. I've seen this before; a number of sites are trying to stop scraping – perhaps because of the AI companies doing this too much? – and thus refuse requests from read_html.

However, the same companies allow you to retrieve using the requests library. I'm not sure why they make this distinction, but I'm guessing that part of it has to do with the different User-Agent header that is sent as part of the HTTP request.

Regardless, this meant changing my strategy a bit: I would use requests.get to retrieve the data. That would return a "response" object, from which I can retrieve the text with the text attribute. I would then hand that text to read_html.

But it turns out that read_html no longer wants to take a string value. Upon trying to do what I just described, I got a warning from Pandas saying that read_html shouldn't be given a string, but should instead be given an io.StringIO object.

Now, I'm a big fan of io.StringIO, which is basically an in-memory string with the API of a Python file object. StringIO is especially useful in testing and on sites like the Python Tutor, which doesn't allow for the use of actual file objects. I ended up with the following code:

all_dfs = []

for one_url in urls:

print(f'Processing {one_url}...')

one_df = (pd

.read_html(StringIO(requests.get(one_url).text))[0]

)

all_dfs.append(one_df)The good news was that this worked: After running this loop, I had all_dfs, a list of data frames that I could combine into a single one.

Let's dig into the call to read_html a bit deeper:

- I invoked

requests.geton the URL. That returned aresponseobject. That object contains all of the information about the returned values, including it status code and response headers. But what interested us here was the actual content that was returned. You can get that with thecontentattribute, but that returns a bytestring. You can instead use thetextattribute to get it as a Python string. - However, as I mentioned above,

read_htmltoday prefers to get a file-like object, rather than a string. I thus created aStringIOobject, passing it the text from the response we got fromrequests. - The result of invoking

read_htmlis a list of data frames. The TSA's page only contained a single HTML table, which meant thatread_htmlonly created one data frame. But it always returns a list of data frames, which means that we had to retrieve the one we got with[0].

If you're wondering why I used a for loop, rather than a list comprehension, the answer is the print invocation at the top of the loop. I like to get that sort of update when I'm running over a number of values, just to know for sure where I am in the loop and where things might go wrong.

But there were two problems with this code: First, the Date column was still considered text, rather than datetime values. Second, I wanted Date to be the index.

I thus invoked assign, assigning back to the same column (Date), which meant that I replaced it. The replacement was the result of invoking a lambda expression on the original Date column, one which invoked pd.to_datetime on the text. In other words, we took strings containing datetime information and converted them into datetime values, assigning the resulting series back to Date – converting our string column into a datetime column. I then invoked set_index to turn the Date column into the data frame's index:

all_dfs = []

for one_url in urls:

print(f'Processing {one_url}...')

one_df = (pd

.read_html(StringIO(requests.get(one_url).text))[0]

.assign(Date = lambda df_: pd.to_datetime(df_['Date']))

.set_index('Date')

)

all_dfs.append(one_df)Now that all_dfs is a list of data frames, one from each of the TSA's pages, we can combine them. The easiest way to do that is with pd.concat, which takes a list of data frames as input and returns a single data frame.

However, pd.concat joins them as is, in whatever order we had. For our purposes, we want the data frame's rows to be in chronological order, sorted by date (i.e., the index). For this reason, I then invoked sort_index on the result of pd.concat, resulting in a sorted data frame, which I assigned to df:

df = pd.concat(all_dfs).sort_index()The result was a data frame of 2,520 rows and 1 column. I could have turned it into a series, but I'll be adding some columns to the data frame later on, and thus decided to keep the single-column data frame.

Finally, I wanted to create a line plot showing how many people travel through TSA checkpoints on each day. I used Plotly Express to create this line plot, invoking px.line and passing df['Numbers'], the only column in our data frame:

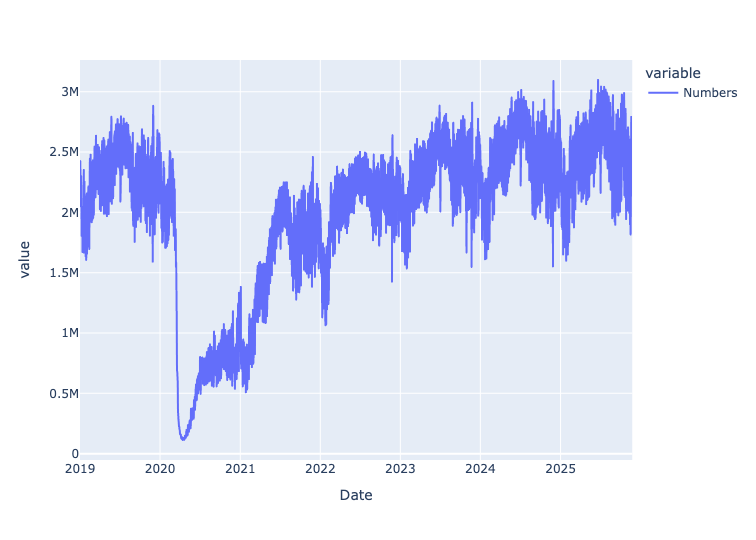

px.line(df['Numbers'])Here's the result:

You can see the dramatic drop in air travel at the start of 2020, when the covid-19 pandemic started and shut down most travel. More people are flying, at least in the US, in 2025 than were before the pandemic, but it has taken a few years to fully recover from that shock.

Add a boolean column, is_thanksgiving, whose value is True on Thanksgiving day itself for the years in question and False otherwise. Add a second boolean columns, is_near_thanksgiving, whose value is True if the date is within four days of Thanksgiving. If you are doing this before data for Thanksgiving has been published, then just repeat the most recent value through Thanksgiving Day of this year (i.e., Thursday, November 27th). Recreate the line plot, but assigning the color based on the value of is_near_thanksgiving. What do you see?

There are a number of ways to add a column to a data frame. One is to just assign a series or list to the column, using [] syntax. Assuming the series or list is the same length as the data frame's index, it'll work just fine.

You can also, instead, assign a scalar value to the column. In that case, every row in the new column will contain that value.

A slight variation on this approach, which we saw above, is to use the assign method. That creates a new data frame, one in which the newly assigned column (or multiple columns, if you pass several keyword arguments) exists. I'm normally a big fan of using assign, but there are cases when it isn't quite as appropriate.

Adding the is_thanksgiving column is an example of where assign isn't as appropriate. I did this in three steps:

- I got the dates for Thanksgiving from 2019 through 2025.

- I created a new column,

is_thanksgiving, and gave it the valueFalsefor all rows. - I then used fancy indexing, passing the dates that I had collected for Thanksgiving, and assigned them all the value

True.

df['is_thanksgiving'] = False

df.loc[['2019-11-28',

'2020-11-26',

'2021-11-25',

'2022-11-24',

'2023-11-23',

'2024-11-28',

'2025-11-27'], 'is_thanksgiving'] = True

However, this didn't quite work. That's because the TSA posts data several times after the day itself. Which means that when I downloaded the data, we had information through November 24th of this year. I wanted to include Thanksgiving of this year, for which we didn't yet have data.

My solution was to add three more rows to df, each with the value of the previous day's travel numbers. I did this by passing a string describing the date to pd.to_datetime, using that as the index, assigning the value from the previous day:

df.loc[pd.to_datetime(

'2025-11-25')] = df.loc['2025-11-24']

df.loc[pd.to_datetime('2025-11-26')] = df.loc['2025-11-25']

df.loc[pd.to_datetime('2025-11-27')] = df.loc['2025-11-26']With those in place, I was then able to perform the full assignment:

df['is_thanksgiving'] = False

df.loc[['2019-11-28',

'2020-11-26',

'2021-11-25',

'2022-11-24',

'2023-11-23',

'2024-11-28',

'2025-11-27'], 'is_thanksgiving'] = True

I could then get all of the Thanksgiving days in the data set with:

df.loc[df['is_thanksgiving']]What about finding dates near Thanksgiving? This turns out to be a lot trickier! I started by creating the is_near_thanksgiving column, assigning it a blanket value of False:

df['is_near_thanksgiving'] = False

I then got all of the actual Thanksgiving dates by retrieving the index where is_thanksgiving is True:

thanksgiving_dates = df.loc[df['is_thanksgiving'] == True].index

I then used a for loop to iterate over each of these dates. For each, I found the date that was 4 days earlier using pd.Timedelta and assigned it to start_of_range. I then did the same thing to find the date that was 4 days later, and assigned it to end_of_range. I used print to display the range over which I was working, to help with debugging.

And then I used .loc with a slice, and assigned True to all of the dates within that range of ±4 days of Thanksgiving:

for date in thanksgiving_dates:

start_of_range = date - pd.Timedelta(days=4)

end_of_range = date + pd.Timedelta(days=4)

print(f'Setting from {start_of_range} to {end_of_range}')

df.loc[start_of_range:end_of_range, 'is_near_thanksgiving'] = TrueFinally, I recreated the line plot. With several columns involved, I needed to be a bit fancier, first invoking reset_index to move it back to being a regular column. Then, in my invocation of px.line, I indicated that the x axis should be Date, and the y axis should be Numbers. Then I asked for the color to be set to is_near_thanksgiving. I even added the hover_data keyword argument, so that we could find the actual Thanksgiving days:

px.line(df.reset_index(), y='Numbers', x='Date',

color='is_near_thanksgiving',

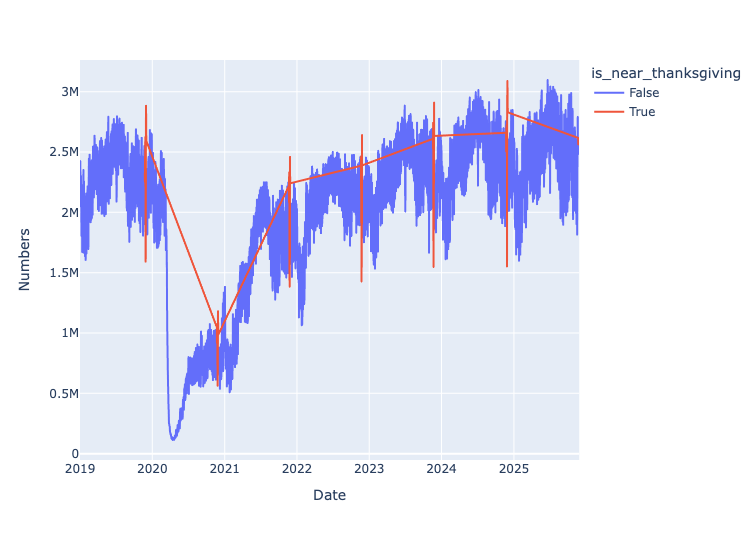

hover_data=['is_thanksgiving'])The result:

Plotly drew a separate red line, which isn't quite what I had in mind, but was good enough for our purposes. And you can see that when it around Thanksgiving, we see a real pop in travel just before... and then a real decline on Thanksgiving Day itself. Which matches what many people see, namely less traffic on Thanksgiving but a real upswing just before.